In the Archives

Mapping the Stars

Mortum Caelum translates to “dead sky,” but it never felt lifeless to me. It was the sky where the departed climbed, a second geography suspended over the first. That became the seed for The Hierophant: a night canopy so crowded with history that its constellations cast shadows on the world below. Water signs stretched into oceans, legendary hunters hardened into nations, and every myth became a draft for a new culture.

Going beyond the surface

Those early drafts lived in sketchbooks long before The Hierophant’s plot found them. I’d trace constellations, shade in continents with colored pencils, and then set loose whatever campaign or speculative idea I was toying with. The setting cycled through fantasy bestiaries, prehistoric survival epics, even science projects. It waited, patient and unused, until the book’s central theme clicked: What happens after death?

Once I started comparing afterlife calendars, the map came alive. Forty-nine days in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, forty for Eastern Orthodox judgement, seventy for an Egyptian embalming, thirty for Jewish sheloshim, eleven for the śrāddha rites in parts of India. Every tradition marked time differently, but each assumed similar tiers of nearness to the sacred. My notes circled a common intuition:

The layered afterlife and cosmological systems arise from the suspicion that reality is stacked in ascending degrees of closeness to the sacred, Mircea Eliade’s ladder between the sacred and the profane, and that the soul’s journey is an upward movement through each chamber of truth.

So what does that first chamber look like? Religions have been sketching it for millennia.

| Tradition | Phrase | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Mesopotamian | Šamû šaplû | The lower heaven |

| Ancient Hebrew | Raqia | Lowest vault of heaven |

| Zoroastrian | Asman girda | The round sky |

| Ancient Greek | Aither hypatos | The lower aether |

| Ancient Egyptian | Pet | Where the sun travels |

| Vedic / Puranic | Bhur-loka | The lowest world |

| Islamic | As-sama ad-dunya | The nearest heaven |

| Cree | Atchakosak Kiskinohamâkewin | The star world |

| Ojibwe | Giiwedinong | The north sky |

| Lakota | Mahpiya | The visible sky (akin to Pet) |

| Diné | Yádiłhił | The lowest emergence sky |

| Yolŋu | Wangarr Djulpan | The star camp in the sky |

| Tiwi | Murrakupupuni | The sky world above |

And the list keeps going. I’m drawn to how broad the consensus is: no matter the language, people keep pointing to a lowered sky that doubles as a waiting room. That common thread is the compass I keep following.

Mapping accuracy

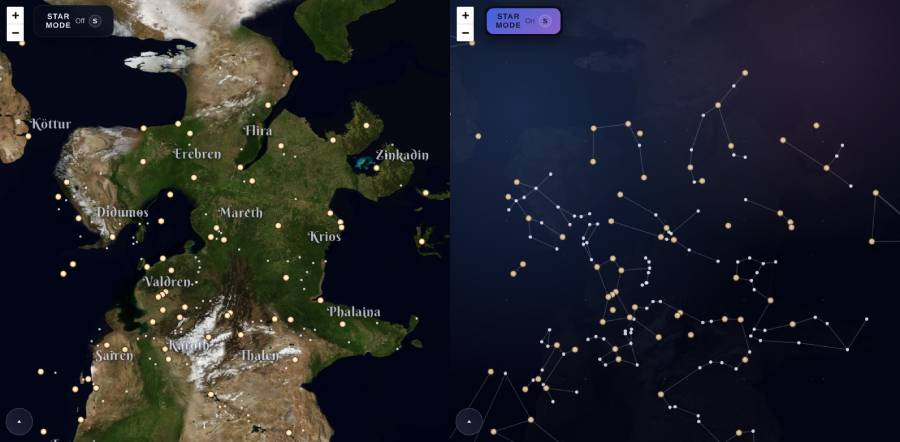

Trading colored pencils for a digital atlas created its own headache. The map begged for a “show me the stars” toggle, but my ancient coordinates were… guess work. Teenage me converted right ascension and declination into latitude and longitude on a TI-83, which was fine for doodles and terrible for precision.

So I tore it apart.

I rebuilt the math from scratch, piped in modern star catalogs, and wrote a converter that projects celestial coordinates onto the Mercator grid that Leaflet expects. Then I nudged continents across 190 degrees of longitude, reshaped coastlines, and started reconciling the geography with lore I’ve added over the last few years. It’s messy right now, but useful mess often is.

If you poke the map today you’ll catch it mid renovation: shorelines half-drawn, city labels migrating, mountains waiting for their ridgelines. Hit the “S” key anyway. Star Mode still works, and seeing the constellations flood the world never gets old.

Share

Signal boost this chronicle entry.

Your voice carries farther than mine: thanks for passing it along.